There’s no debate that what Naughty Dog was trying to do with The Last of Us Part II was contextualize the violence, and in some ways make the player feel bad for the cycle of violent behaviors and murder being perpetrated. It’s a game that wants you to feel empathy and to see the nuanced greys of both sides. The Last of Us Part II wants to erase the binary concept of heroes and villains through perception and added context. But The Last of Us (and more so, Part II) is not about roleplaying as these characters. It’s not about becoming Ellie. We as the player are simply passengers along for the ride. When you accept that we are not Ellie, The Last of Us Part II’s story is allowed to resonate.

Spoilers for The Last of Us Part II follow.

The biggest and most obvious difference between movies and games is watching versus participating. It’s somewhat the difference between sympathy and empathy (though the true nuances of that are far deeper and require a whole different conversation). In film, we are simply observers of a story. We understand that we sit outside of that box, watching these characters through window and a lens. When it shows us the character’s depths, we understand and accept that we are observers. In games, we become those characters. We intrinsically link them with ourselves. Their actions take on a new meaning because we as the player are the ones perpetrating them.

But what about that space in between observation and roleplaying?

The Last of Us is not our story. It’s Ellie’s story. It’s Joel’s story. It’s Dina and Jesse and Tommy. It’s Abby and Owen and Lev. It’s a character story, made up of many individualized people. We may be put in their shoes, but we are never meant to “be” them. But at the same time, we’re not meant to simply observe. Naughty Dog offers context through action and engagement. We’re a passenger along for the ride, occasionally asked to take the wheel for a bit, but ultimately driving towards the same conclusion by predefined characters. We don’t have any choice in the matter, and it challenges what it means to roleplay as a character in a video game, often justifying any and all actions we (or rather, the avatar on the screen) takes.

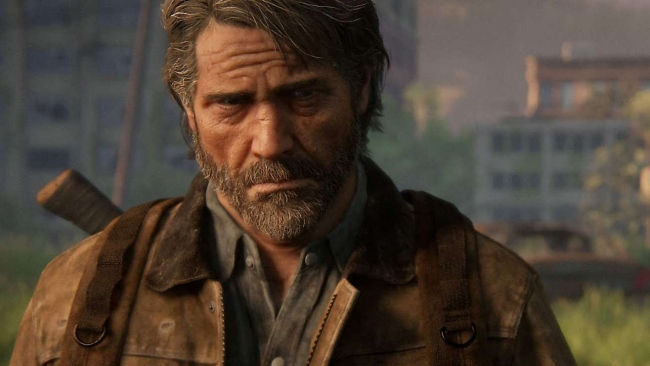

And so the controversy surrounding The Last of Us Part II’s story centers on players (or readers of Wikipedia) wanting control of that story. They don’t feel that Joel “deserved” to die. They question the motives and actions of characters through their own lens based on what they would do or they would want. But it’s not our story. We aren’t them. We have no control. Joel died, whether he deserved to or not. Abby’s father died, whether he deserved to or not. Jesse died. Manny. Owen. Mel. The question of whether or not these characters “deserved” their fate is one of perception. Naughty Dog was never trying to tell a fan-service story to please the people who thought Joel was a hero. They were trying to tell the natural progression of a story whose characters are human.

In the first game, Joel does what he does. He kills the doctor—Abby’s father—and players are forced to do it to progress that moment and finish the game. It’s not a cutscene, but it’s not a choice either. In that moment, you are a passenger. You may have your hand on the wheel, but Joel is driving. His decision is his own. And it catches up with him. He doesn’t die some magnificent heroic death. Because this isn’t just his story. He’s not the hero. He’s just a man who’s made some choices leading to that moment where his timeline ends.

But his end isn’t truly the “end,” which is why the moment occurs early on. His life and death, his decisions and those of the people around him have rippling effects. Naughty Dog knew that many players identified with Joel, being the main protagonist of the first game. So they killed your heroes. The team never wanted to “satisfy” players. They wanted to challenge them.

Naughty Dog didn’t just want to challenge the perception of wanton video game violence, but also the more meta level “roleplaying” aspect that people take on with games. From the get go, very early on in Part II, players take control of Abby, pushing her towards what will inevitably be Joel’s death. Which then begs the question: is that on you, the player? After all, you played as Abby. You pursued Joel and Tommy. You led them back to her group. So it’s your fault. Except that it’s not. You were a passenger. Like a film, you were being made to observe Abby, whether you wanted to or not. You were never meant to “become” her, but your actions pushed her towards the inevitable, connecting you with the moment in a deeper way than film ever could. It’s about understanding her, whether you agree with it or not. Joel’s death is a done deal. It’s not a Schrodinger’s Box or a player choice. The only real “choice” you have is to simply turn off the game.

‘She Wouldn’t Have Done That’

Moreover, many of these online voices seem to criticize the choices players make. But the thing is, they did? None of the choices made are entirely out of character. There’s always a level of bias we’ll project on characters for the “perfect” outcome, but humans are imperfect, unpredictable, and far more nuanced than we give fictional stories credit for. How many things within your own life—either yourself or the people around you—have seemed “out of character?”

The overwhelming fact is we’ve only seen a fraction of these character’s lives. We aren’t these characters and we simply aren’t in their heads. Naughty Dog never fully and completely meant us to be.

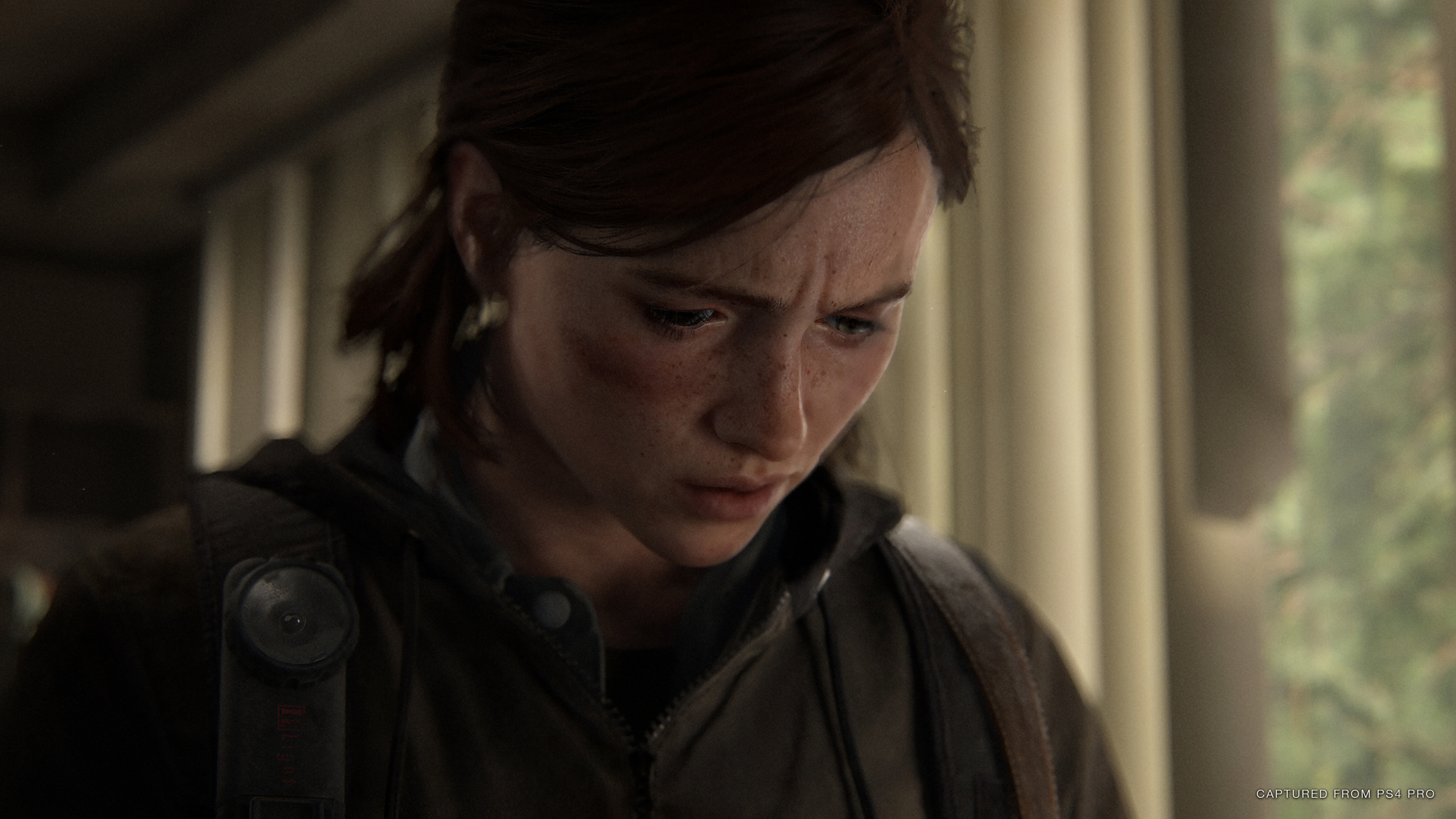

Ellie’s overwhelming rage at Joel’s death was never just about Abby murdering Joel. Over the course of the game we’re treated to flashbacks that reveal how much Ellie truly knew about Joel’s decision to save her. GameSpot’s Phil Hornshaw wrote a great piece examining this narrative structure, and while I agree with everything he’s saying, I want to look at it from a slightly different perspective. Phil’s criticism of the narrative is that Naughty Dog was not up front about how much Ellie knew before the end of the game. We as the player believe her motivations to be a bit more ambiguous, before being fully aware that she knew Joel’s death was a direct result of him rescuing her.

But if we were playing as Ellie, shouldn’t we have been aware of her motivations and knowledge completely?

We Don’t Live in Their Heads

Not necessarily. As passengers, we have no choice in the final destination, and that extends to us not needing to know everything about why characters are making the choices they make. If observation is third-person and roleplaying is first-person, Naughty Dog achieved a second-person narrative that falls in between the two. We are Ellie, but we don’t quite know what’s going through Ellie’s head. We are Abby, but we’re not quite sure of her motivations either. It’s empathetic observation through forced interaction, much like the much-memed “Press F to pay respects” from Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare. We don’t need to agree with the actions, but we need to take them anyway. We’re not observers. We’re not roleplaying the choice. We’re an active passenger.

When Ellie finally settled down with Dina, I was thrilled. This is what Joel died for. He rescued Ellie so she could live her life with someone she loves. But Ellie relapses. Without the quest for vengeance to focus that anger, she has PTSD, not just about Joel’s death, but also about his rescue of her. See, Ellie’s rage was never 100% about Joel’s murder. It was Ellie’s way of working through myriad feelings and emotions, a complicated internal conflict of being angry at Joel for what he did and angry at Abby for taking him from her. So many things were left unresolved. She was still angry at Joel, but she knew it was a moment that couldn’t be taken back. How could she reconcile that? Trust me, it would have been much easier if it was a simple revenge plot. But it was never that simple and Ellie was left shattered and conflicted, to the point that the life and love she was given could never overcome it.

I didn’t want her to leave and continuing pursuing Abby. But I was forced to go along with it. Again, a passenger. It’s not my story to tell. And yet there’s a kind of dark irony in Ellie’s decision. While she may have lost everything, she also eliminated a gang of sadistic kidnappers, and ultimately rescued Abby and Lev, who surely would have died without her help. It’s in direct contrast to the end of The Last of Us. There, Joel takes a villainous action because of love, and gains a lot from it. In The Last of Us Part II, Ellie takes a heroic action because of hate, and loses everything because of it. It’s not black and white. There are no heroes and villains. There are only humans.

The Last of Us Part II works best when you stop “being” the characters, when you stop roleplaying as them and take a step back. When you realize that these characters are not and were never meant to be you as the player. Naughty Dog told a story in a wholly unique way that only games can accomplish, neither fully letting us become these characters, but also never allowing us simply observe either (which is why a Wikipedia summary of the narrative loses its impact). It’s an in-between state meant to make us uncomfortable and challenge our usual empathetic perceptions. The Last of Us Part II is a game meant to be played, because its strongest beats require that the player be interacting directly with the narrative, even if they have no control over which way it’s going to go.