An increasing common tale in the games industry is that developers are quitting their jobs in AAA game development to go indie. It’s a risky move, and one that has developers giving up a guaranteed gig to pursue their passion. Daniel Weinbaum, who was formerly an environment artist at Infamous developer Sucker Punch, recently released his first PlayStation 4 game since leaving the studio called Leaving Lyndow. We’ll have a review up later today, but first we talked to Weinbaum to learn why he left the studio to pursue the uncertainty that is being an indie dev.

PlayStation LifeStyle: You used to work at Sucker Punch. Can you talk about your background, and working for that studio?

Daniel Weinbaum: I was at Sucker Punch for a little over a year, and I was an environment artist. Anything you see in the game that’s not a person like a fire hydrant or a building, I would make that kind of stuff. I got that job right after working for a small outsource studio, and I had gotten that job after spending one year at ArenaNet as an intern. So, I had done environment art for three and a half years in AAA development.

Did you leave AAA development because you wanted to do more since I see a lot of people get fed up with doing just one thing and then move into the indie space?

DW: Yeah, for sure. You definitely do one thing. Once you get into the industry, once you’re hired for something, if you want to do something else well chances are you’re not very good at doing it since you don’t have experience. That’s not very helpful for the company since you’re not good at it, so it’s very hard to branch out. My desire to leave, and I love environment art and Sucker Punch was a great company, but I really wanted to make my own game. Everyone wants to make their own game, I think, but I just wanted to do it really, really bad. It’s something I’ve wanted to do since I started my career.

I think it’s a noble undertaking, especially from an artistic viewpoint, to give up a guaranteed paycheck at a AAA studio and then take a chance to bet on yourself. How worrying was that to you before you left?

DW: That’s the hardest thing, and what I think deters so many people from going indie. It was worrying, but I always knew I wanted to do my own thing. I always thought it would cost a lot of money, and I knew nobody would just come along and give it, so I had been saving religiously my entire career. I was planning on giving it a go when I was like 40, but when the indie scene started, I saw so many people making ambitious games that I thought would be really hard with a small team, but they were doing it.

It made me think I could do it to, and I started messing around with CryEngine. I felt like I was making good progress, and I had all this money saved up that was meant to be used when I was older, but it was enough for my own personal burn. So, I figured if I quit my job, burn all my life savings so far and fail, then that’s okay since it’s what I want to do. I felt that not doing it was worse than doing it and failing, which led to me making that decision.

I love this story since I can sort of relate to it. Since I quit my job to get into games journalism, and I love seeing people bet on themselves. Did you always have the idea for Leaving Lyndow when you left Sucker Punch?

DW: I didn’t always have the idea. We had been working on a larger title called Eastshade, which is what I started right when I quit, and I had been working on that for two and a half years. Then I realized that I had been working on this game for a really long time, and still had a long time to go. It’s uncommon for your debut game to take that much effort, and since I had never shipped a game, I knew we’d mess some stuff up. A lot of stuff you don’t think about initially like doing press releases, and pushing updates. I knew there’d be a learning curve, and didn’t want to be learning while putting out a game I put all of my life’s savings into.

So, how can we ship a game, a smaller game, that people will like without starting from scratch. So, I decided to do a prequel, that would give people a taste of what we’re doing while also being its own thing. Something we could learn to ship a game on, so that we would be better on it for Eastshade. So, that’s how I started thinking about making a smaller game.

One day I was browsing Steam, and I found this short 20 minute Gone Home like experience called Home is Where One Starts. I really liked it, enjoyed the format, and loved having a new experience for just 20 minutes. I think there’s a critical lack of short games like that. So, I was inspired to do it from a business perspective, since I wanted to learn how to ship a game, and from a creative perspective, as I thought we needed more short games.

My big takeaway from Leaving Lyndow was that it’s very much like a short story. Do you feel like gaming, as a medium, should be used more often to give players glimpses of worlds, and be more like a short story?

DW: Yeah. I really like that format. I like how it works for a game. Short stories don’t really tell a story necessarily, they don’t have plot twists or character development, they just nail a feeling. That’s what I was trying to do with Leaving Lyndow. I really like games like that, but I don’t think that’s how gaming will go since it seems that everyone hates them. I didn’t expect that the largest criticism for Leaving Lyndow was that it was too short and that it didn’t amount to anything. If they don’t like it then I probably won’t be doing another game like that. It just seems that people aren’t interested in it, just I am, and you are too.

One thing I thought was really smart was how you decided to ship a game before your first major product. When you have total freedom, I feel like it’s easy to get overwhelmed by things. How do you make sure that you balance that, and make sure you’re not overworking yourself?

DW: It’s hard. Your money is always burning, so you don’t need anyone to crack the whip. But in terms of staying sane, I don’t know. I’m not really a workaholic, but I like what I do and still have time to go on trips and go camping. I’m not really the type of personality to have a problem with it. It is hard to decide what to do since you can do anything. Oh, you just want to stop the game you’re doing, and do some small project instead? You can do that if you want to. In our case, it seemed like there were enough reasons to do Leaving Lyndow that it made sense.

What were the biggest learning experiences for you going through cert, and releasing on Steam & consoles?

DW: For PC, it was learning the Steam backend. Even uploading a build to the server is pretty complicated. I would not want to be frantically trying to learn that right before launch. For example, we had the soundtrack as a separate product on Steam. I pushed an update for the game, but little did I know I also updated the soundtrack with an empty folder. It deleted the soundtrack off of everyone’s computer. So, you can imagine what a disaster a much larger launch would be.

In terms of the PS4 release, there is so much to learn. Every little thing is so big. Like making sure the icon for the save file is the right resolution seems dumb and little, which it is, but if you do it wrong then it’s a two-week turnaround to go through certification again. So, if you have a release schedule, it can be really devastating. I think it would’ve been suicidal to do that with a game 10x as large.

With regards to Leaving Lyndow, I knew your background beforehand and I couldn’t help but see some poetic tie-in from the game’s story of leaving a life behind, and then you leaving Sucker Punch to go on your own adventure. Was that on purpose, or am I just overthinking it?

DW: That makes total sense but I’ve never thought of it that way. I was thinking more about leaving for college, as she’s sort of young and coming to age, but I never really thought of it as an analogy of leaving AAA gaming.

You get a glimpse of a larger world in Leaving Lyndow, and it definitely raises more questions than answers. I get why that would frustrate some people, but I enjoyed getting to see that. Are we gonna return to that world in Eastshade?

DW: Yeah. Leaving Lyndow takes place in the island of Eastshade. In that game it’ll be totally open-world, and you’ll be able to talk to most people. You’ll be able to go to all of the places you wanted to go to in Leaving Lyndow, but couldn’t.

How many people worked on the game?

DW: My girlfriend helps a lot with the writing and the UI. She’s an art teacher by trade, so she helps a lot with that and quest design. I also have a character artist since I’m not experience at that, a composer, and Charlene, who does the publicity for us.

In the future, do you want to work with additional people on projects?

DW: It’d be really nice to be able to outsource some things, but I can’t imagine a situation where we can handle the burn of having a space and having people full-time. I would have to constantly worry about if all the pistons are running, and we’d have to make a lot more money. I really like the way we currently do it, and it’s been very fun. If I never make enough to hire others, that’s fine. I’d be totally happy to do this until I die, and make all kinds of weird, new games and work in my underwear.

I did run into some technical issues on the PS4 version, how difficult has it been learning to do a game and not just environmental art?

DW: It ran much better on PC, but the console porting process was really hard for me. By the time it was working, I did some performance modifications, but I hit a point where I just had to ship it since people were waiting for Eastshade and I can’t take forever. I had a couple people play it and they were happy with the performance, I thought it was a little bit jerky, but they thought it’d be alright. So, I hear that [criticism] loud and clear. That’s something I’ll nip in the bud for Eastshade.

One of the most misunderstood parts of gaming is the porting process. A lot of gamers don’t think there’s much work in it. Can you speak to those challenges?

DW: A lot of things add up. If you build your game from the ground up for mouse and keyboard, that can have really big consequences on how your UI is structured. So, we had to make sure that everything worked with the analog sticks. That’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Other things, like how trophies work. You have to use the API (Application Programming Interface) that Sony gives you, and you need to implement that into your game. Stuff like hitting the PlayStation Share button, and making sure that happens. Also, when the game launches it needs to tell the PlayStation Network that you’re playing this game. That doesn’t even include the fact that the current generation consoles, the GPU in there is less powerful than most people’s gaming computers, so you have to be really tight with performance. In some cases the graphic APIs might not line-up, and that’ll have big consequences on what shaders you’re using. It’s a really big job.

You mentioned that you don’t feel there’s a market for short games. How has the feedback been from both consumers and those in the industry?

DW: I don’t think my friends would tell me I didn’t like it. They know how hard it is to make a game almost by yourself, and they just want to be supportive of the fact that we managed to do it at all. In terms of critics, when we launched on PC, the reviews were better than expected. I thought there’d be complaints that it should’ve been free, even though I picked a price that I thought was fair and what I’d pay. I expected more backlash, but people liked it. I’m happy with our reception, we had a 74 on Metacritic, which is just below when the game turns green. That actually makes a big difference to people psychologically, but still, I was really pleased with it. Reception on the PlayStation 4 has been a lot lower. We’ve gotten scores below 50, and I guess that can be attributed to it being a different audience.

When do you plan on launching Eastshade, and what can we expect in terms of gameplay?

DW: I tell myself that we’re launching February 2018. I know we’ll probably not make that, but if we launch in 2018 then we have to do it in the first half of the year. We’ll have to wait until 2019 if not since we’ll be buried by AAA games. It’d be suicide to launch during the [back half of the year] when we’ve put so much into the game.

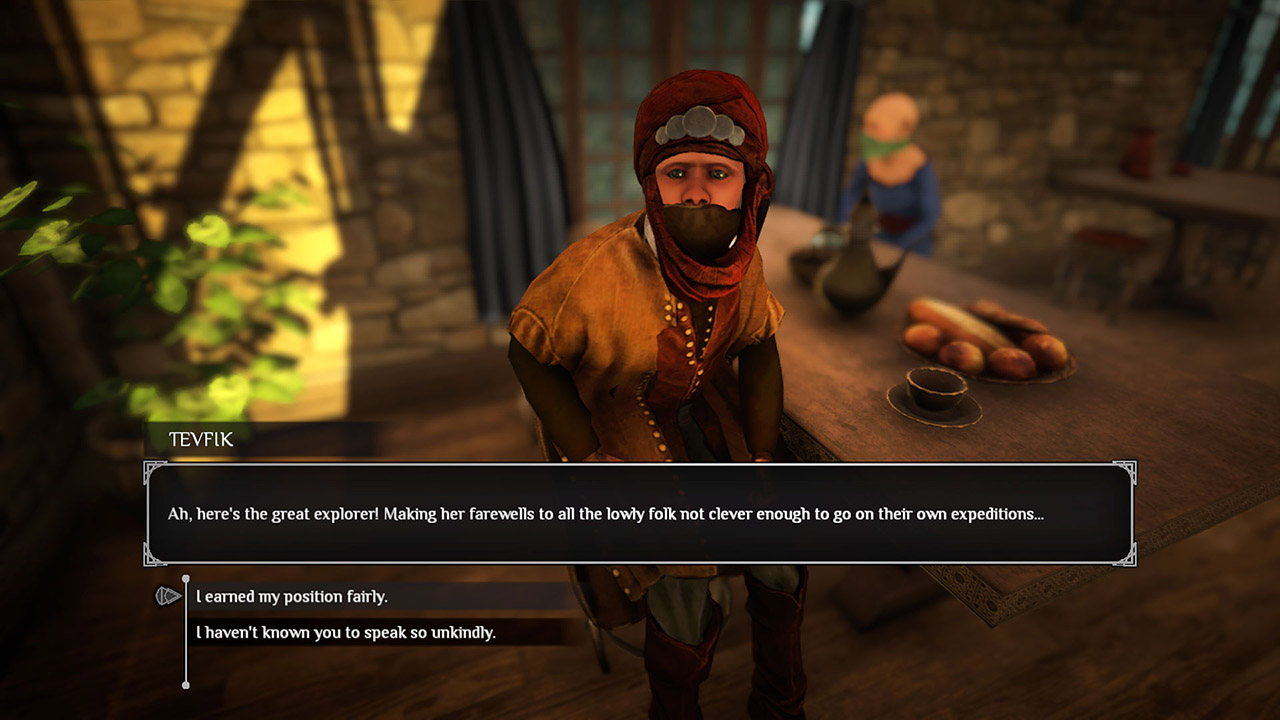

It’s going to be much bigger, and much longer. Mechanically, it has little to do with Leaving Lyndow. It plays a lot more like Morrowind. Imagine a much smaller version of Skyrim, on a smaller island. There’s a bunch of micro-stories you can take part in, and it’s almost like a travel simulator. Go to a new place, see what’s up, and that’s what people can expect. We’re trying to hit the six-hour mark in terms of content.

I’m really impressed by your business acumen. I see so many games launch immediately after it finishes with no press releases or build up, but you get the importance of that.

DW: I do a lot of research, and Charlene makes sure we don’t do anything extremely stupid. It’s very important.

Why should players give Leaving Lyndow a shot?

DW: It’s like a cup of coffee. It’s not a systemic game, or a clever story. It doesn’t have a big twist like “Oh, it was Vanessa all along!” It doesn’t have those moments, but it’s a feeling. It’s interesting, and I think it’s worth someone’s time (45 minutes to an hour) and is worth $4. If you go into it with the feeling of just visiting somewhere then I think you’ll get more joy out of it.

PlayStation LifeStyle would like to thank Daniel Weinbaum for taking the time to talk to us. Leaving Lyndow is available now on PlayStation 4 and PC, and Daniel can be found on Twitter @Eastshade.